Alfred Cove is a residential suburb of Perth named after a small sheltered bay which is located on the Swan River and has clear views to the CBD. Within the suburb is a reserve which comprises a tiny remnant of tidal marshland surrounding the bay and extending about fifty metres inland from the shoreline. The reserve is covered in low salt tolerant Samphire and other vegetation along with a tree-line of larger Sheoak and Eucalyptus trees which form a dense protective barrier.

The Resident Male Osprey

Black Winged Stilt

Caspian Tern

The area is under pressure from invasive species, weeds, domestic cats, dogs, foxes, recreational use, drainage issues and all the usual environmental threats associated with close proximity to high density housing and traffic. Located in the heart of our city, it is literally a tiny remnant of the extensive tidal marshes which originally surrounded the margins of the Swan River before the land was developed.

Little Egret

Red Necked Avocets

White Faced Heron

Within this tiny area there are mudflats, sandy flats, beaches, marshy intertidal zones and remnant bushland. The diversity of habitat provides an extremely valuable refuge for a diverse array of creatures, especially birds. Consequently, the area is inhabited by bush birds, sea birds, raptors, waterbirds and migratory waders.

Black Shouldered Kite

White Faced Heron

A trip to Alfred Cove will usually result in sightings of Great Egrets, Little Egrets, White Cheeked Herons, Yellow Billed Spoonbills, Pelicans, Darters, Little Pied Cormorant, Great Cormorant, White Ibis, Pelicans, Caspian Terns, Fairy Terns, Osprey and Black Winged Stilts.

Yellow Billed Spoonbill

Little Egret

Osprey

It is also common to see Red Necked Avocets, Pied Oyster Catchers, Red Capped Plovers, Buff Banded Rails, Greenshanks, Black Headed Cuckooshrikes, Goshawks, Black Shouldered Kites, and Banded Stilts along with numerous bush birds.

Yellow Billed Spoonbill

Black Winged Stilt

Yellow Billed Spoonbill

Alfred Cove is an important feeding ground for migratory waders which traverse the globe in an annual migration between their feeding grounds in Perth and their breeding grounds in the Arctic tundra. Bar Tailed Godwits, Grey Plovers and Red-Necked Stints arrive from August onwards. They remain here over the summer, leaving our shores to fly North and breed around April. In the past year I was lucky enough to photograph Grey Plovers and Bar Tailed Godwits at Alfred Cove. It is fascinating to think that such small and unassuming birds make this epic journey every year. Here is a link to maps showing the incredible migratory routes of these birds;

Grey Plover - Pluvialis squatarola

Bar Tailed Godwit - Limosa lapponica

The abundance of small fish in the bay make Alfred Cove an ideal feeding ground for piscivorous species. It is common to see Great and Small Egrets along with White Faced Heron stalking schools of small fish in the shallows. Egrets employ a few different fishing techniques, one of which is to wait by the entrance of tidal pools and catch the fish being drawn in or out by the tide. The tides in the Swan River are quite variable. At extreme high tides the area floods and you see Swans and Pelicans swimming over what is usually boggy marsh or dry land. At extreme low tides a sandbar emerges and extends a long way out into the centre of the river. At these times, I have noticed the number of Egrets in the area increases dramatically as the shallow water and sandbars work in their favour to trap fish.

Great Egret Fishing

Great Egret - Breeding Colours

Little Egret

At dawn every morning, the resident pair of Osprey leave their nest on a pole and fly high over the bay in search of breakfast. Once they spot something they will descend a little lower and then lower again before dropping vertically with talons outstretched ready to grab the fish.

Osprey on the Hunt at Dawn

There is usually a huge splash and the bird often disappears under water for a few seconds before emerging to unfurl its wings and struggling to become airborne with the extra weight of water and fish. Very rarely, they will catch two fish at a time, one in each talon.

Osprey

Osprey

Osprey

Once airborne the Osprey will shake mid-air to remove the excess water and fly back toward his nest or a nearby pole with the struggling, wriggling fish clasped firmly in its talons. Photographing Osprey fishing requires quick reflexes and a lot of luck. It is difficult to predict where the fish will be caught and exactly which direction they will fly in from but, if you watch them closely and sit on the shoreline often enough opportunity does present itself.

Osprey with a Goatfish

Once perched, the Osprey will spend an hour or so eating the fish, an activity that usually attracts the attention of Seagulls and White Faced Heron which converge beneath to grab the scraps. The Ospreys do not seem to share their fish. I have often observed one watching the other eat and squawking in a high pitched tone as if begging. Sometimes the Osprey with the fish appears to get annoyed at this behaviour and will take off to a more distant perch to finish the fish in peace. Occasionally a rogue Osprey will fly in into the area to fish. The resident pair actively defend their territory and I have often observed dramatic aerial fights as they battle it out in the sky. At one point a rogue Osprey was flying in at exactly 7am every morning. He was an extremely efficient fisher and would almost always catch a fish on his first dive and leave quickly flying out in the direction of Point Walter.

Osprey with a Goatfish

Sometimes huge flocks of Cormorants Pelicans and Seagulls descend on the bay in a feeding frenzy which is spectacular to watch. I have observed that there are often dolphins about when this happens and wonder if they deliberately herd the fish into the enclosed bay so they are easier catch. I have seen this happen a few times and watched as the chaotic flocks of birds move around the bay following what must be a large school of small fish. At these times the peaceful bay is transformed into a whirling, noisy, splash filled cacophony of life doing it's thing.

Pelican and Little Black Cormorants

It is common to see Caspian Terns flying in huge arcs around the bay and then dropping in a dramatic vertical dives to emerge a few seconds later from the huge splash with a tiny fish. They are magnificent to watch with beautiful feathers in shades of white and soft grey contrasting with a bright red beak. I have spent hours watching them dive on the other side of the bay too far away to photograph. They always seem to be just out of reach, but experience has taught me that if I turn my back one will invariably dive right behind me in what would have been the perfect shot if only I was looking.

Caspian Tern

Caspian Tern

Caspian Tern - Emerging from a Dive

In the right season the Fairy Terns bring their babies to the shores of the bay and teach them to fish. I have observed parent Fairy Terns fly out and catch a fish, then return to the shore flying low over their squawking babies before returning back out over the water. As the babies watch their parent flying off into the distance with the fish they are enticed to follow. Once the baby is flying out over the water, the parent bird will drop the fish encouraging the baby to dive for it. As the babies begin to associate diving with food they start to catch their own fish. It is wonderful to see.

Fairy Tern - Adult & Juvenile

Fairy Tern - Adult & Juvenile

Fairy Tern - Adult and Juvenile

Photographic opportunities at Alfred Cove are endless, diverse and unpredictable........from the dramatic moment the Osprey catches his fish, the silent intent focus of Egrets stalking their prey, the super fast vertical dive of Terns fishing, stunning reflections of Waders, storm clouds over the city, tiny shells and insects, debris washed up on the beach and so on and so on.

Blue Banded Native Bee

As a photographer you become acutely aware of light, its quality, colour, tone, intensity, angle and direction. I believe the quality of light and how it is utilised in an image is probably the most important thing in photography. Light will make or break an image. I am always looking at the sky and studying how the available light illuminates subjects and how this changes depending on the relative positions of me, the subject and the light source.

Something quite ordinary can be transformed into a stunning vision in the right light, while something rare, unusual or dramatic can look completely boring in bad light. Depending on weather conditions, the light of the early morning and late afternoon is usually the most beautiful, carrying rich subtle tones which highlight detail and colour. In my experience, Images taken at those times are much more likely to be keepers.

Darter

Unexpectedly, I have also found that overcast weather often creates exceptional light for photography because it gets diffused and reflected in all directions by the cloud causing the subject to glow and removing harsh shadows and extreme contrasts. This is particularly relevant when photographing white birds and evidenced in my photography where many of my very best images have been obtained under overcast stormy skies.

Black Shouldered Kite - Photographed in Heavy Overcast Conditions

Little Egret - Photographed in Cloudy Conditions - Non Directional Light Made him Glow

Photographing White Birds - Exposure Issues

Exposure can be difficult to get right when photographing white birds. There is an enormous amount written on this subject on the web by people that have far more technical knowledge and understanding of photography and cameras than me, so this is just a brief non technical discussion of what works for me so far........ I find that photography is a constant learning process and I am continually learning new techniques and tricks.

I always photograph in full manual mode. While this is probably the side effect of being a closet control freak it is very useful when photographing white birds because I have become very familiar with quickly manipulating exposure manually by adjusting shutter speed, ISO aperture.

The Problem with White Birds

Camera light metering systems are extremely sophisticated but generally do not cope well with subjects that are very light or very dark especially when they fill a large proportion of the frame or occur together. This is because automatic metering systems are calibrated to produce an exposure value based on the mid-tone of the frame content. So if your frame content is highly skewed toward dark or light the automatic exposure readings will be inaccurate.

Little Egret

Little Egret

There are three situations with white birds that I face regularly. Firstly, if you have a white bird against a dark background the camera will tend to excessively overexpose the bird. Secondly, if you have a white bird against a light background the camera will tend to underexpose the bird. Finally if you have a white bird in bright sunlight the camera tends toward overexposure often blowing the highlights. Spot metering modes, can compensate for all of these situations to some degree by giving the camera more information on which to base its calculations, however I have still found that with white birds you can't really believe the exposure meter.

Great Egret Against a Light Background Settings ISO 500, 260mm, f6.3, 1/3200

Spoonbills Against a Very Dark Background Settings ISO 1000, 400mm, f8, 1/3200

Consequences of Incorrectly Exposed White Birds

If a white subject is overexposed, the highlights are blown out and you are left with a very bright white monotone area that has no detail whatsoever. In these situations, the detail is simply not there so cannot be recovered during processing. If a white subject is underexposed it will be rendered a flat dirty grey colour. Lightroom is great for correcting exposure, however, I always keep two things in mind. Firstly, if the highlights are blown due to overexposure, the detail is generally not recoverable, and secondly, while adjusting exposure up is often quite successful it increases noise and consequently reduces the overall quality of your image.

Yellow Billed Spoonbill

How I Deal With Exposure When Photographing White Birds

Given a choice between potentially overexposing or underexposing white birds I always adjust settings to underexpose, sometimes by quite a bit. This is partly because I tend to prioritise a high shutter speed for birds in flight but also because I have found that a badly underexposed image can usually be recovered in Lightroom while an overexposed one can't.

Great Egret

Little Egret

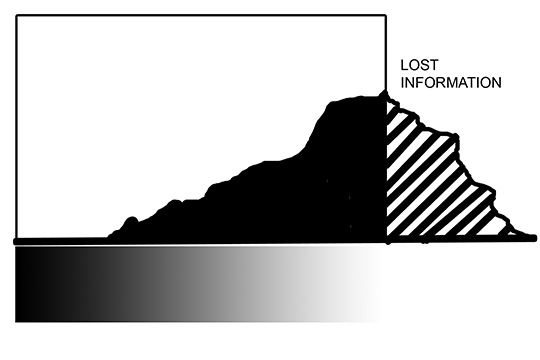

When photographing white birds, I tend to take a few shots at varying exposures (changed by adjusting ISO, Fstop, Shutterspeed) and check them on the screen. This usually gives me a good indication of what my settings should be but is not completely reliable so I also check the histogram. This gives me a visual representation of the exposure and a measure of any detail lost by over or under exposure. When a histogram cuts off at the right the image is overexposed and conversely when it cuts off to the left an image is underexposed. The degree a histogram is clipped indicates the amount of detail lost from either the highlights (on the right) or the shadows (on the left).

Histogram Indicating Over Exposure and Loss of Detail

Histograms for Underexposed, Correctly Exposed and Overexposed Images

I find these basic checks give me a pretty good indication of what I can get away with as far as underexposure goes and definitely show up blown highlights so I can avoid overexposure. In nature photography things happen very quickly and you do not always get time to check your settings in detail. If there is no time to go through the checking process I have described I always err on the side of underexposure often by quite a bit.

Little Egret in bright sunlight - Camera Settings; ISO 320, 400mm, f11, 1/3200

When photographing white birds in bright sunlight the possibility of overexposure is magnified due to the bright reflective quality of the feathers. I have found this to be particularly relevant for Egrets which are a very pure bright white. In situations like this, light is plentiful, so I can choose my favoured high shutter speed of 1/3200 and then drop the ISO to about 200 and increase the f-stop dramatically. A lot of literature suggests avoiding white birds in bright sunlight. Despite this, I have found that with these general settings I can get images that are exposed correctly and are extremely sharp due to the increased depth of field and contain heaps of fine intricate detail due to the low ISO. It is definitely worth experimenting with.

Great Egret in bright sunlight - Camera settings; ISO 320, 400mm, f10, 1/3200

To conclude, Alfred Cove has taught me an enormous amount about photography and birdlife. I am very lucky, it is only two minutes drive from my office, a beautiful peaceful place full of life and the origin of some of my very best images. It has also been a place where, for me emotions are calmed and the acute stillness which pervades the landscape works its magic on my mind by cutting through superficial concerns and anxieties to the deeper subtle layers where you can appreciate the beauty that is all around us.

The City Viewed from Alfred Cove at Dawn

A Pair of Yellow Billed Spoonbills Together in Flight